From Henry Ford’s Five-Dollar Day to its unprecedented manufacturing efforts in support of Allied forces during World War II, Michigan spent decades as a hotbed of American industrial innovation. But despite its 20th-century dominance over American mechanized production, Detroit lays claim to surprisingly few unique and well-known inventions. Even the car wasn’t invented here; Hank and company simply figured out how to do it quicker than anybody else. Perhaps its most iconic export—Motown Music—is automotive-adjacent in name only. Enter the Michigan Left: This is not so much a deliberate invention but a serendipitous byproduct of a now-defunct transportation strategy that left southeast Michigan with one of the largest, most underutilized road networks in the country.

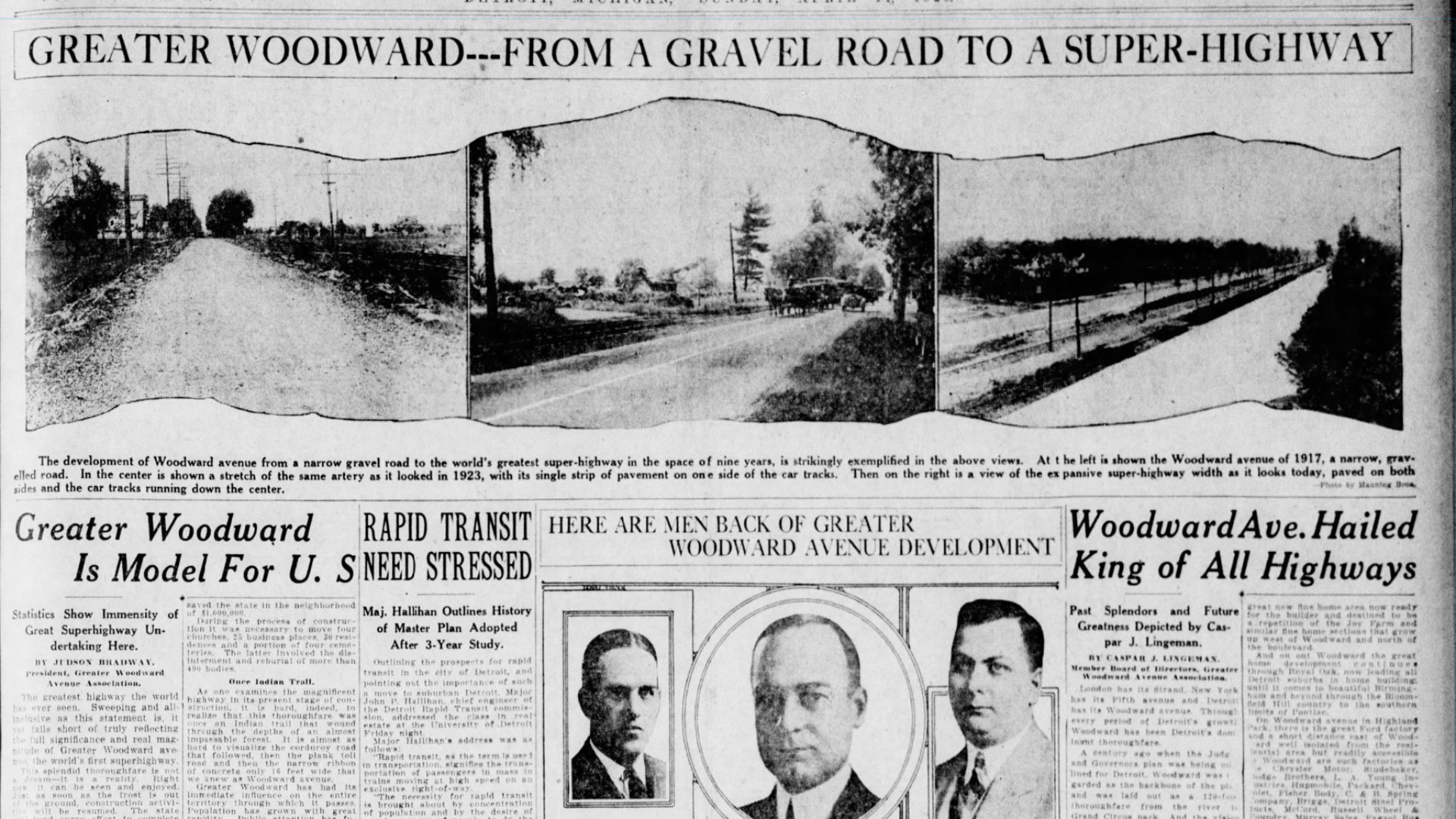

As Detroit grew rapidly during the automotive boom of the 1910s and 1920s, its planners sat down with others in the region and conceived of something that would radically change how its citizens got around. It was called the superhighway, and it was the key element of perhaps the single most ambitious regional mass transit system ever proposed in the United States.

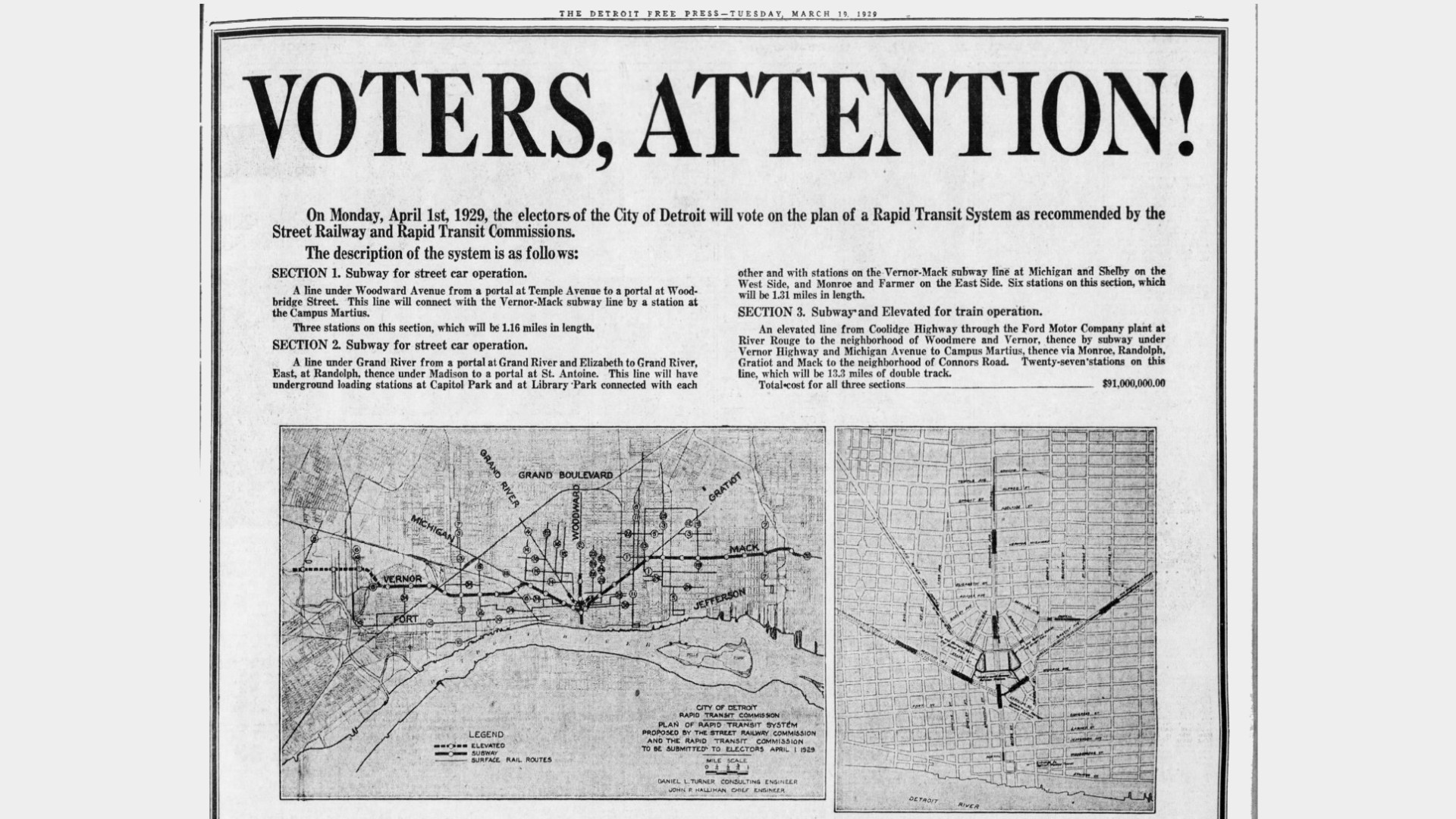

That’s right—Southeast Michigan’s sprawling grid of “Mile Roads” was conceived not merely as a means of circulating private vehicle traffic, but as a holistic regional network consisting of surface rail, subways, streetcars, and, yes, automobiles. By the mid-1920s, Detroit was expanding so rapidly that its planners were looking well into the future. Detroit’s population was already approaching one million people, and some of its more enthusiastic supporters were projecting a population north of 10 million by the year 2000. That never happened, of course, but Detroit residents clamored for wider thoroughfares as the old roads were quickly choked by commuter traffic.

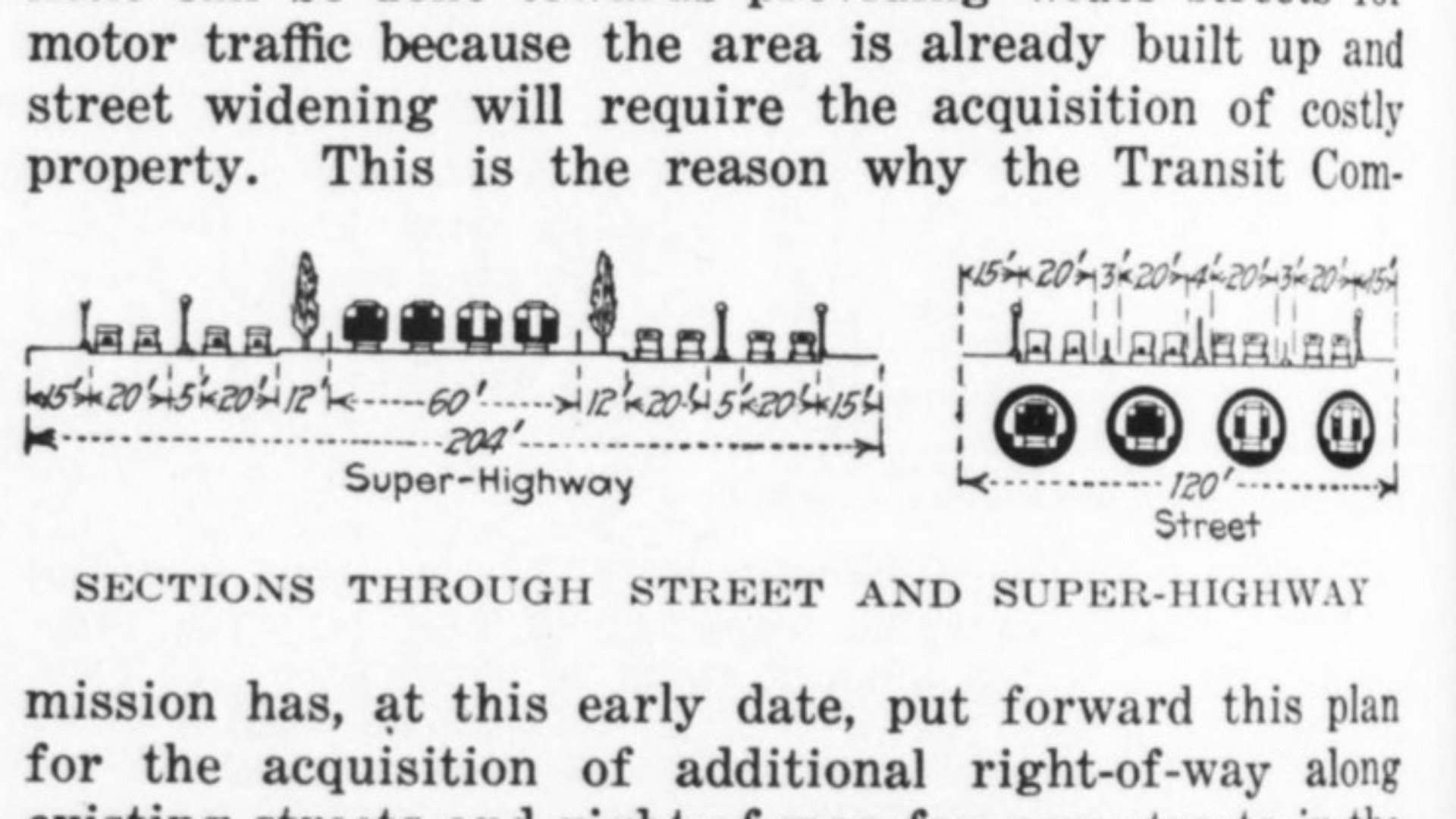

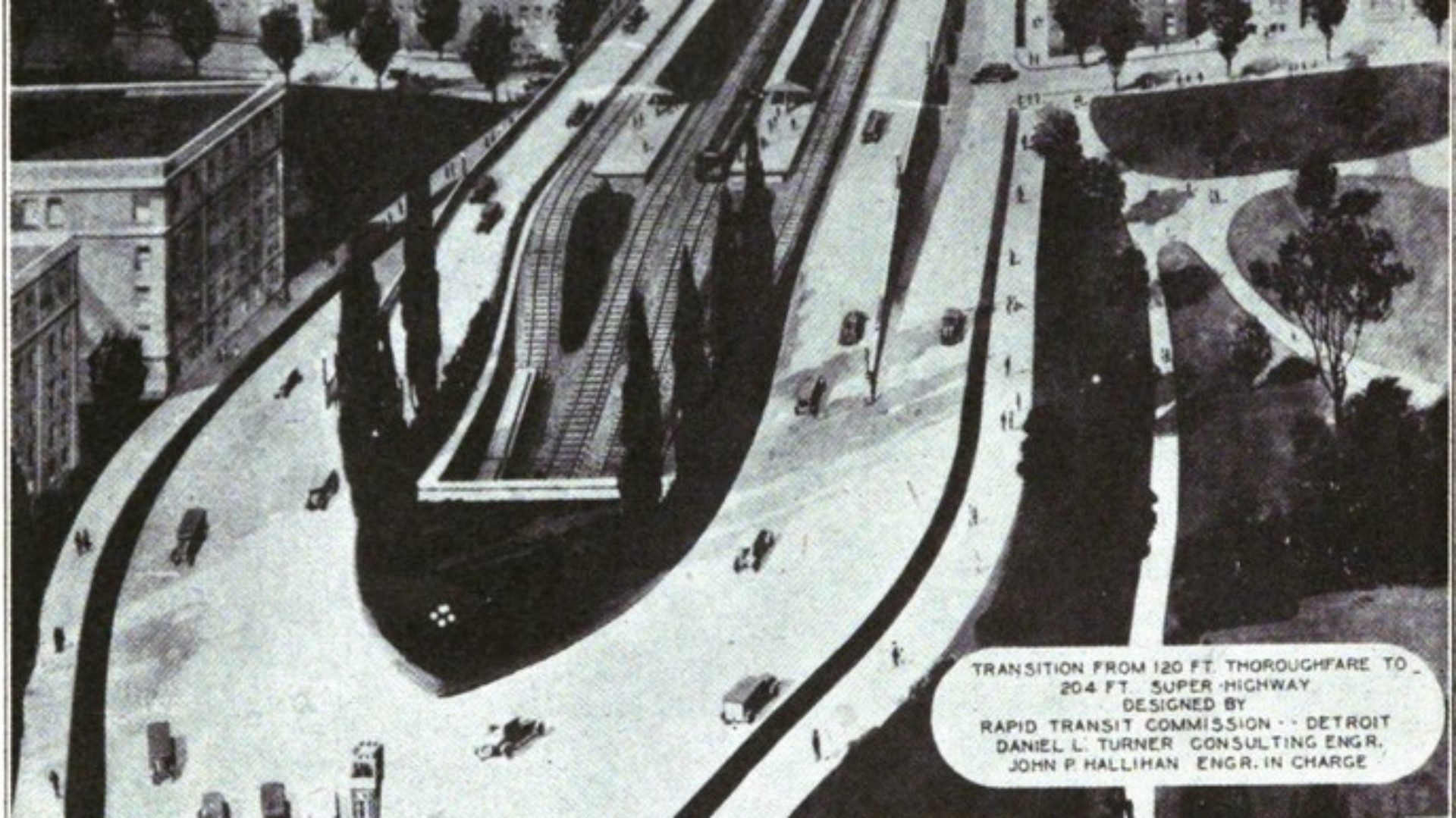

Local commissions embraced the fundamentals of the plan, and initiatives were launched to widen Detroit’s existing avenues. The new and improved Mile Roads alternated between 120 and 240 feet wide. The former would allow as many as four subway lines to run underneath while still maintaining space for other major infrastructure (water, sewer, etc.); the 240-foot variant could accommodate four lanes of automobile traffic in both directions, up to four rail lines (or a two-track station) in the median, and still had ample room to expand underground or above it. The major Detroit avenues radiating out from downtown, including Woodward, Gratiot, and Grand River, would form the connector spokes of this vast new “superhighway” network. Many of these routes had existing streetcar and inter-urban rail service, which was usually incorporated into the new footprint with ease.

Today, the term “superhighway” has fallen out of fashion. Detroit’s early prototypes had a lot of elements we commonly associate with limited-access freeways today, including wide medians and intersections with minimal or zero conflicts, but they were also meant to remain accessible to both surface traffic and pedestrians.

Early versions of the plan stipulated that all of the major mile-road intersections would be grade-separated interchanges (think highway cloverleafs, only for surface avenues), but these notions evaporated when representatives appointed to oversee the project saw just how much that sort of infrastructure would cost. Instead, only a few of Detroit’s major surface “superhighway” intersections would get that treatment. Today, many of those old interchanges are being replaced with low-conflict alternatives that are more budget-friendly, such as the diverging diamond just recently completed at 8-Mile and Telegraph Road on the city’s border with Southfield.

To make matters worse, Detroit wouldn’t vote on the transit plan until 1929—a year after the market crash that precipitated the Great Depression. The transit plan failed to pass the city council by just one vote. As land speculation along the highways dried up and previously eager project boosters evaporated, southeastern Michigan’s planning committees would need to come up with more fiscally responsible ways of linking all these major arteries together. After stripping back the flyover bridges, railroad stations, and subway tunnels, there was one vestige of this grand design that still made a lot of sense.

The Michigan Left

It’s a simple concept, but brilliant in its execution. Like New Jersey’s “jughandle,” the Michigan Left’s primary advantage is the elimination of left turns at major intersections. Rather than waiting to turn left against cross-traffic, drivers turn right, then use a dedicated U-turn lane in the road’s median to double back in their intended travel direction. This not only reduces the wait for left-turning drivers, but it makes it possible for the traffic light to cycle faster because through traffic never has to wait for those turning left.

The above video uses Macomb County’s Hall Road as its example, but thanks to Detroit’s early Superhighway plan, many of its Mile Roads had ample room to implement this setup, and with timed traffic lights, they allow these major arteries to function a lot like the highways their original designers envisioned, only without all of the integrated transit that necessitated those wide medians in the first place.

Instead, what Detroit’s failed transit grid gave us was the earliest version of what we know today as a “Stroad“—a thoroughfare that hybridizes a street and a road. In urban planning parlance, a street is designed for everybody’s use—pedestrian, automotive, transit, etc.—while a road is something meant more exclusively for high-speed traffic. It’s a dirty word to many burgeoning urban planners, but here on the outskirts of the Motor City, it’s a label we’ll embrace, because hey, our stroads are just a little bit better than yours.

Got a tip? Email us at [email protected]