J.D. Power released the results of its 2025 Initial Quality Study on Thursday, and—surprise, surprise—the number one reported problem area industry-wide is infotainment. While the systems themselves are becoming more visually impressive and they’re better-integrated into the overall design of most vehicles than early attempts, customers complain more about these systems than they do anything else in their brand-new cars. In short, customers love the way these big screens look, but virtually all of them are a pain to operate.

So why the heck does every new car introduction come with a bigger, more feature-bloated touchscreen? Well, it’s complicated. But as usual, it all comes down to money.

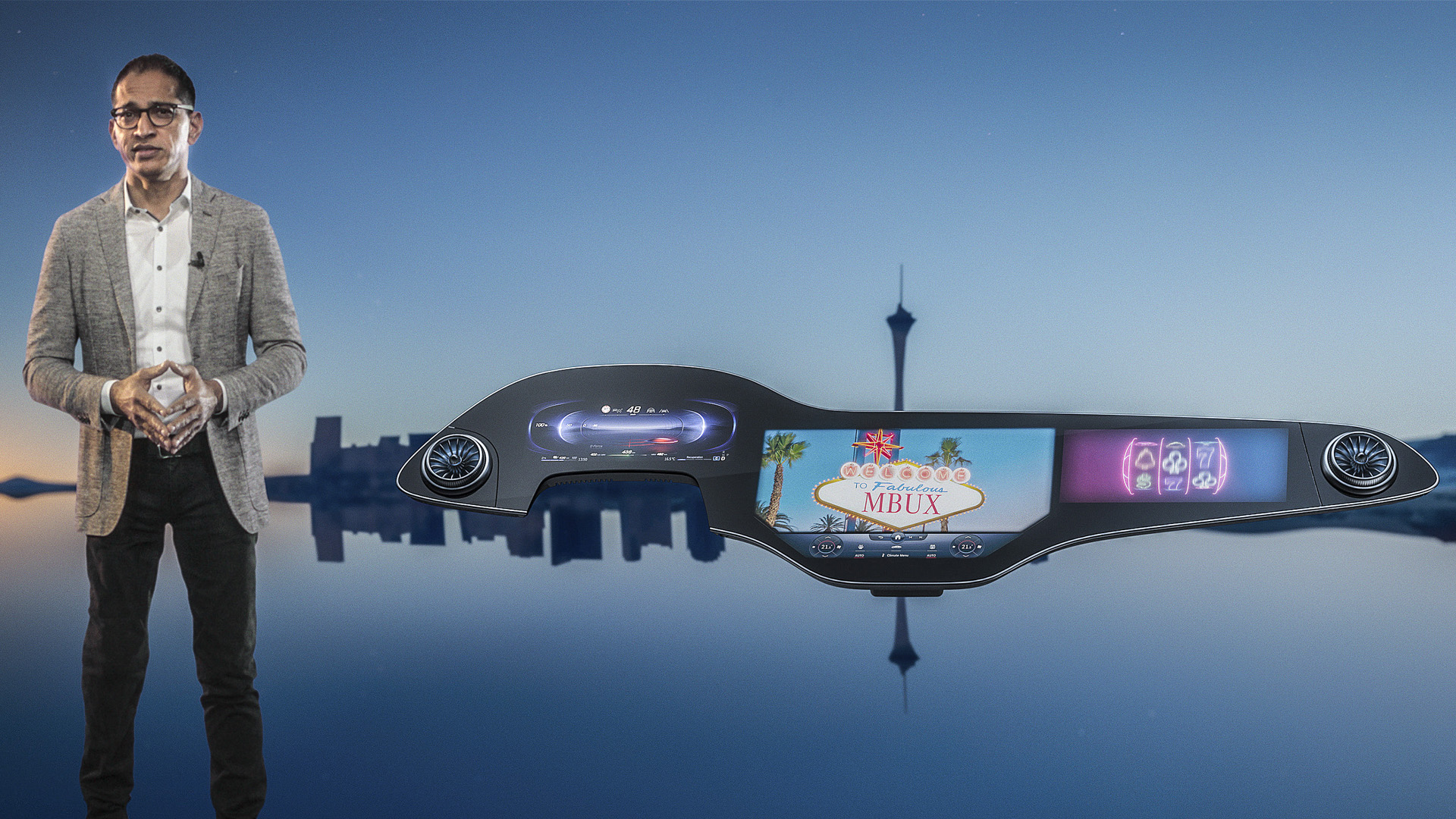

The “why” makes more sense if you consider the broader industry push to re-brand the traditional (spits) infotainment system as an all-in-one control center. Functions that were once tied to physical controls on the dash and center console have been steadily migrating into this space. Headlight toggles, home garage door controls, and even glove box releases are now making their way into vehicular touchscreen interfaces, in many instances joining basic audio and climate controls that were moved there years ago.

Automakers sell it as a way to free up space on the dash and center console. For what? So far, the answer has mostly been “more screens.” One might call that a lateral move. With all the extra room, you’d think they’d be able to keep up with America’s fancy cup obsession. And given the positive feedback automakers have received for the more-minimalist interior designs that often result, the effort hasn’t entirely been for naught.

Plus, centralized touchscreen control systems save automakers money, especially when implemented in cars with a broad selection of available doodads. While software development isn’t free, it’s far more forgiving than designing, prototyping, testing, sourcing and maintaining a supply of physical control components. An infotainment module may cost more than a switch, but you’d be surprised how quickly that math changes when one switch becomes five—or fifty.

But in designing for this internal convenience, automakers are taking a gamble that their buyers will learn to live with the resulting compromises. What’s often left unsaid is the fact that we’re increasingly running the risk that a failed infotainment system could effectively “brick” a car completely. And eliminating those physical controls doesn’t eliminate the need for them, forcing automakers to add new infotainment menus, tiles, and pages—and in some cases, entirely new screens—that its customers must then navigate. This clutter annoys critics and customers alike.

“Owners find these things to be overly complicated and too distracting to use while driving,” said J.D. Power’s Frank Hanley, senior director of auto benchmarking. “By retaining dedicated physical controls for some of these interactions, automakers can alleviate pain points and simplify the overall customer experience.”

But even as some automakers pledge to bring buttons back, there’s no reason to expect they will come at the expense of established display real estate. Even if customers are frustrated by the experience offered by their large displays, they still enjoy looking at them, and as those screens get bigger and bigger and take over space that was once reserved for other features, those features will have to go somewhere. Right?

With each generation, more features are incorporated into the screen. To avoid excessive menus, the screens get bigger to accommodate those new functions. It’s an endless cycle fueled equally by feature bloat and the desire to cut potentially redundant physical components—which equate to finding ways to charge more money for less car.

And then there’s the unspoken financial opportunity presented by a more robust digital infrastructure. Unless you’ve been living under a rock your entire life, you know by now that a screen is always at risk of becoming a new avenue by which somebody can sell you something. New features? Maintenance plans? Subscription services? Those are all tough to sell through a button. Just ask GM.

So as you read the next car reveal, and you peruse the interior section to see what inconveniences await its new buyers, remember that a bigger screen does three things: it sells new cars to wide-eyed customers, saves the automaker a ton of money on components, and it offers the tantalizing possibility of future revenue streams.

Nope, these screens aren’t going anywhere.

Do you also like to yell at clouds? Commiserate with the author at [email protected].